Our Water Future: The Effort to Preserve a Vital Resource

The water crisis is at our doorstep, and it’s up to us to find a solution.

Too long, didn’t read:

Water scarcity is a growing problem impacting agriculture, economies, and ecosystems, with no easy solutions and conflicting approaches to water preservation.

The Aral Sea disaster serves as a stark warning of the consequences of prioritizing short-term economic boom over water longevity.

Collaborative solutions like the Sheridan 6 LEMA show that reducing water use is possible without sacrificing profitability—aligning economic incentives with resource prosperity is key.

Water: A Defining Challenge for an Entire Generation

Water scarcity is the defining challenge of our generation. It’s a problem that touches everything—from food production to economic stability. Unlike many other pressing issues, there’s no arguing over the urgency of this one. Water shortages are a reality that everyone can agree on, no matter where they’re located or what their political views are. That agreement shows just how serious the situation is. But recognizing the problem is the easy part. The real work begins when we start looking for solutions. Water is crucial for life, agriculture, and industry, yet overuse, poor management, and unpredictable weather patterns are stretching our resources thin. With populations growing and demand rising, the question isn’t whether we need to act—it’s how we can come together to ensure a stable water supply for the generations to come.

The real roadblocks? First, there’s no easy fix. And second, no one agrees on the best way forward given the difficulty of addressing the problem. While it’s easy to see that one exists, proposed solutions spark heated debate. Some push for stronger government intervention, believing regulations and policies are the only way to manage water equitably and effectively. Others argue for market-driven strategies, advocating for private property rights and economic incentives to encourage preservation. More on that later… First, let’s look at one of the many environmental catastrophes related to water…

Disaster on the Aral Sea: A Mini Case Study

The Aral Sea disaster is a cautionary tale of what happens when short-term agricultural goals take precedence over long-term well-being. Once the fourth-largest lake in the world—larger than Lake Huron, the Aral Sea spanned the border of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, supporting a thriving fishing industry and providing livelihoods for tens of thousands. But in the mid-20th century, the Soviet Union had a different vision for the region—one centered on output, not resource optimization.

Starting in the 1950s, the Soviet government launched an ambitious plan to transform Central Asia into a major cotton-producing region. The goal? Agricultural self-sufficiency and dominance in the global cotton market. To make this happen, officials diverted massive amounts of water from the region’s two major rivers, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya, to irrigate millions of acres of newly cultivated land. At first, the plan seemed successful—cotton production soared. But the cost? A rapidly disappearing Aral Sea.

By the late 20th century, the consequences were undeniable. As water levels plummeted, the once-prosperous fishing industry collapsed—fish catches dropped 60% by 1970, becoming non-existent by the 1980s. Entire communities lost their livelihoods, and what remained of the sea became too salty and polluted to support aquatic life. Today, much of the former seabed is an arid wasteland, prone to toxic dust storms that have worsened public health and further devastated local agriculture.

The rusting fishing boats stranded in the desert stand as a stark reminder of the unintended consequences of large-scale irrigation projects. The Aral Sea’s story is more than just history—it’s a warning. When water management decisions prioritize short-term economic gains over lasting availability, agriculture, communities, and entire ecosystems pay the price.

Why Such a Challenging Problem to Solve?

Addressing water scarcity in agriculture isn’t a simple fix. It’s a tangled web of interconnected challenges. Crop insurance is perhaps the most successful agricultural policy ever conceived, and it’s certainly the most popular with farmers. But the programs are built around historical yields, which unintentionally reward farmers for sticking with the status quo. So, for those who want to transition to less thirsty cropping systems, the financial guarantee isn’t there because they have no history with the new systems. In other words, moving to different practices means smaller insurance guarantees—a real financial deterrent for farmers who rely on crop insurance. This would be true of any transition. And it’s not a knock on crop insurance; it’s just a reality of actuarial science, which relies on loss history to calculate guarantees and rate insurance products. This science is part of what makes crop insurance so successful. But it further complicates an already difficult problem to solve.

But that’s just one piece of the puzzle. The financial ecosystem in agriculture complicates things even more. Banks lend to farmers based on crop insurance guarantees, so when those guarantees drop, borrowing power follows suit. Plus, loan repayment structures often hinge on maintaining or boosting revenue, which can push farmers to prioritize short-term profits over long-term water availability. This pressure is made worse by the structure of agricultural cooperatives and value-added enterprises that are heavily reliant on high-volume production. Farmers whose balance sheets are tied to these ventures may feel the need to keep water-intensive practices in play to ensure volume is maintained, which just perpetuates the cycle.

The landlord-tenant dynamic adds yet another layer of complexity. In areas where share rent agreements are common, landlords might resist tenants’ attempts to reduce water use. They worry that using less water could mean lower yields and, as a result, lower rental income. This disconnect between landlords and tenants over water-saving measures creates a significant barrier to change, even if the tenants understand the need for more sustainable practices. The fear of losing access to land is real, and it can pressure tenants to keep using water intensively.

But there’s more. Legal and policy frameworks also play a role in water overuse. Some states have “use it or lose it” policies for water rights, which push farmers to use as much water as possible to preserve future rights. Even without these policies, the belief that if one farmer doesn’t use the water, a neighbor will, can lead to the dreaded “tragedy of the commons” effect. Add to that the economic logic of immediate profit over future availability, and you’ve got a recipe for unmaintainable practices. In all this, it’s important to remember that farmers aren’t the problem. They’re just responding to the economic signals and policies they’ve been given. The real challenge is redesigning these systems so that economic incentives align with the need for water preservation. That could mean anything from creating financial products that reward long-term water stewardship to revisiting water rights policies to encourage reduced use.

Water Scarcity Goes Mainstream

Water scarcity in agriculture is no longer just a problem in the field; it’s something that’s seeped into our culture, making its way into music, film, and literature. James McMurtry’s 1995 song “Levelland” paints a haunting picture of the consequences of water misuse in farming. With lines like, “Daddy’s cotton grows so high; sucks the water table dry; rolling sprinklers circle back; bleeding it to the bone,” McMurtry makes it personal—and painfully relatable. For me, the song hits home because I’m from Levelland. My dad grows cotton, and like the song describes, our sprinklers circle endlessly, drawing from nearly 42 wells. I can confirm, we’re bleeding it to the bone. The song’s imagery of lush cotton fields and relentless irrigation highlights the troubling truth: a thriving farm that’s living off a resource we’re rapidly depleting.

Hollywood, of course, hasn’t missed the drama surrounding water and agriculture. The 1974 classic Chinatown fictionalizes the notorious California water wars of the early 20th century, mixing corruption and power struggles with the fight for water rights. And for a lighter take on the issue, there’s Rango (2011), an animated film that my kids love. Beneath its quirky surface, it tackles the issue of water scarcity in a pointed way.

Then there’s the real-life story of Stewart and Lynda Resnick, the couple who control one of the largest farming empires in the U.S. and live in Beverly Hills. Even as water in California becomes frighteningly scarce, they have to continue to increase their usage to maintain their business and continue supporting thousands of farmworkers and the small towns they call home. It’s a glaring example of the ethical quandaries we face today: water as both a commodity and a lifeblood of agriculture.

Water isn’t just a resource; it’s ingrained in our culture and the way we live. It’s the most important compound on Earth, and the question is: What happens when it runs out?

Okay, John; I’m convinced. What do we do?

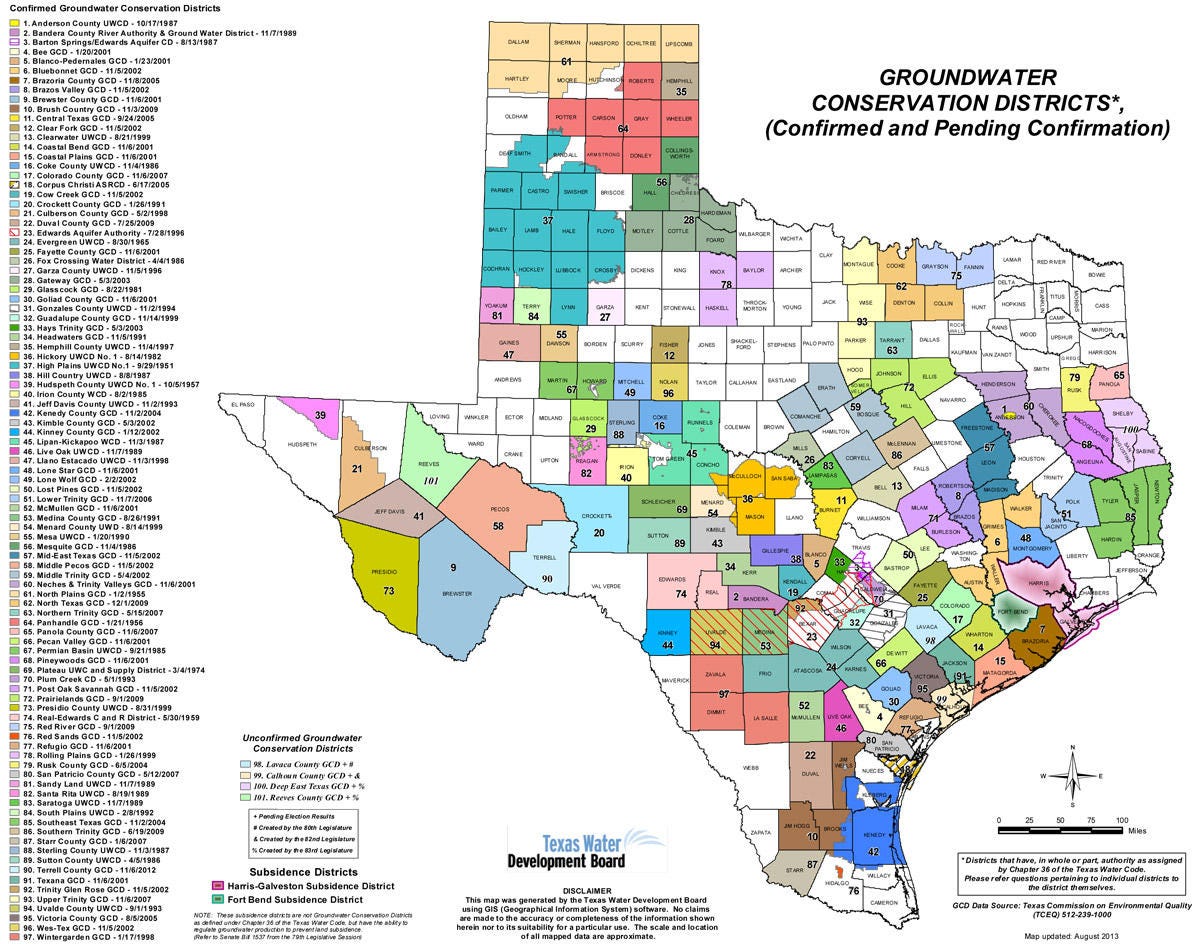

Government regulation is one option. Personally, I’m a small-government, pro-property rights advocate, so government intervention isn’t my favorite option. Addressing the issue this way is no easy feat, especially with the maze of water districts and rules that vary from state to state. Government regulation often leads to long, drawn-out legal battles—especially when it comes to disputes between states. Take a look at the recent Supreme Court ruling on the Rio Grande Compact. The complexities of interstate water disagreements are enough to make your head spin, and when you throw the federal government’s interests into the mix, it only gets messier. This kind of legal limbo can leave water users in the dark for years, with no quick fix for the immediate water management challenges at hand.

A more promising approach could be compensating farmers for pumping less and involving the entire agricultural supply chain in reducing water usage. This approach, which has been championed by the sorghum industry in recent years, focuses on collaboration rather than top-down regulation. It encourages everyone—farmers, processors, retailers, and even consumers—to work together toward water-saving goals. By aligning economic incentives with water preservation across the whole supply chain, we can drive meaningful change without adding more regulatory weight to farmers’ shoulders.

It’s not impossible. The Sheridan 6 Local Enhanced Management Area (LEMA) in northwestern Kansas is a standout example of how communities can tackle groundwater issues head-on. Established in 2013, this 99-square-mile area in Sheridan and Thomas counties set a bold goal: a 20% reduction in water use over five years. The results are impressive. Groundwater use dropped by 23.1%, and the rate of aquifer decline slowed from two feet per year to less than half a foot annually. What’s even more remarkable is that farmers within the LEMA managed to maintain—or even increase—their profits while using less water. They made this possible by adjusting their crop choices, including boosting sorghum production by 335.4%. This success shows that we can make significant strides in water preservation without compromising agricultural productivity or economic stability.

The story of the Sheridan 6 LEMA holds valuable lessons for the broader region, especially for those relying on the High Plains Aquifer. According to the Kansas Geological Survey’s Q-stable model, an approximate 30% reduction in pumping could stabilize groundwater levels in many areas. While this may sound like a heavy lift, the Sheridan 6 example proves it’s achievable and, in fact, can be beneficial for farmers’ bottom lines. These farmers showed that by improving irrigation efficiency, adjusting crop selections, and adopting new management practices, they could thrive with less water. What’s more, if the responsibility for water preservation use is spread across the entire agricultural supply chain—from farmers to processors, retailers, and consumers—this goal becomes even more attainable. A collaborative effort not only makes the shift easier for individual farmers but also ensures the long-term viability of agriculture in areas facing water scarcity.

Takeaways

To wrap up, water scarcity is not a problem we can put off any longer. It’s a challenge that touches everything from our farms to our futures. But here’s the thing: while the problem is clear, the solution isn’t quite as simple. We’ve seen some promising examples, like the Sheridan 6 LEMA, that show what’s possible when we work together—farmers, communities, and even consumers. Their success proves that we can reduce water usage without sacrificing productivity or profits. And it’s not just about cutting back; it’s about making smarter choices, improving irrigation efficiency, and shifting crop choices to better align with the needs of our future. The road ahead may not be easy, but the sooner we get started, the better off we’ll all be.

About Serō Ag Strategies

At Serō Ag Strategies, we bridge farmers and supply chain partners by transforming complex agricultural data and policy into actionable insights. Our approach combines multinational expertise with boutique consulting’s personal touch, specializing in sustainability and economic analysis that drives strategic innovation.

Click here to learn more about Serō Ag Strategies.